12,000,000 BCE

First known cement forms via natural processes, via burning oil shale next to a limestone deposit.

3,000 BCE

Ancient Egyptian use an gypsum mortar to cement the pyramids. Effectively a plaster of Paris containing a small amount of lime.

800 BCE

Ancient Greeks develop lime mortars with crushed pottery acting as an artificial pozzolan.

300 BCE – 476 CE

Ancient Romans use lime cement with added volcanic ash from Pozzuoli, Italy, creating the famous Roman cement.

1200-1500

Much of the knowledge about creating strong cement was lost, however the addition of pozzolan was reintroduced in the 1300’s.

1755-59

John Smeaton experiments with different combinations of limestones and additives and disicovereed the “hydraulicity” of of lime was directly related to the clay content of the limestone.

1796

James Parker created Parker’s “Roman Cement” which would set in five to fifteen minutes. No relation to actual Roman cement.

1824

Joseph Aspdin patented a material he called Portland cement after the island of Portland England.

1843

William Aspdin refines his father’s cement formula, creating modern Portland cement.

1909

Thomas Edison patents the rotary kiln.

Cement has been used by humanity for well over five-thousand years, from the ancient Egyptians, to the Greeks, to the Romans, and even arising independently in Mesoamerica, all the way to the Modern Era. Cement is an integral part of human culture, creating homes, bridges, skyscrapers, and all manner of structures that make modern life possible. Cement is the foundation of society itself.

The very first occurrence of cement is not of human origin. This cement was created twelve-million years ago in Israel where a deposit of oil shale adjacent to a bed of limestone caught fire, transforming the limestone into the first known of cement. Geologists discovered this deposit in the 1960’s (Brewer)

Ancient Egyptians used a primitive precursor to modern cement that consisted of sand and roughly burnt gypsum (which contained some calcium carbonate) when constructing the pyramids. (Hewlett)

Going forward to the ancient Greeks, they improved cement to a mixture of hydrated non-hydraulic lime and pozzolan, creating a very hard hydraulic cement. Pozzolan added to cement creates a pozzolanic reaction resulting in a much harder cement which we know today as Portland Cement. The source of the pozzolan varied depending on what was available. Early on, the Minoans used crushed potsherds as a kind of artificial pozzolan before Romans discovered the natural pozzolanas located near Rome. The Greeks used volcanic tuff found on the isle of Thera as their pozzolan and the Romans used crushed volcanic ash mixed with lime. This Roman cement is world renowned for its ability to set in water and its incredible longevity. The majority of still standing Roman ruins are made of this material. (Hewlett)

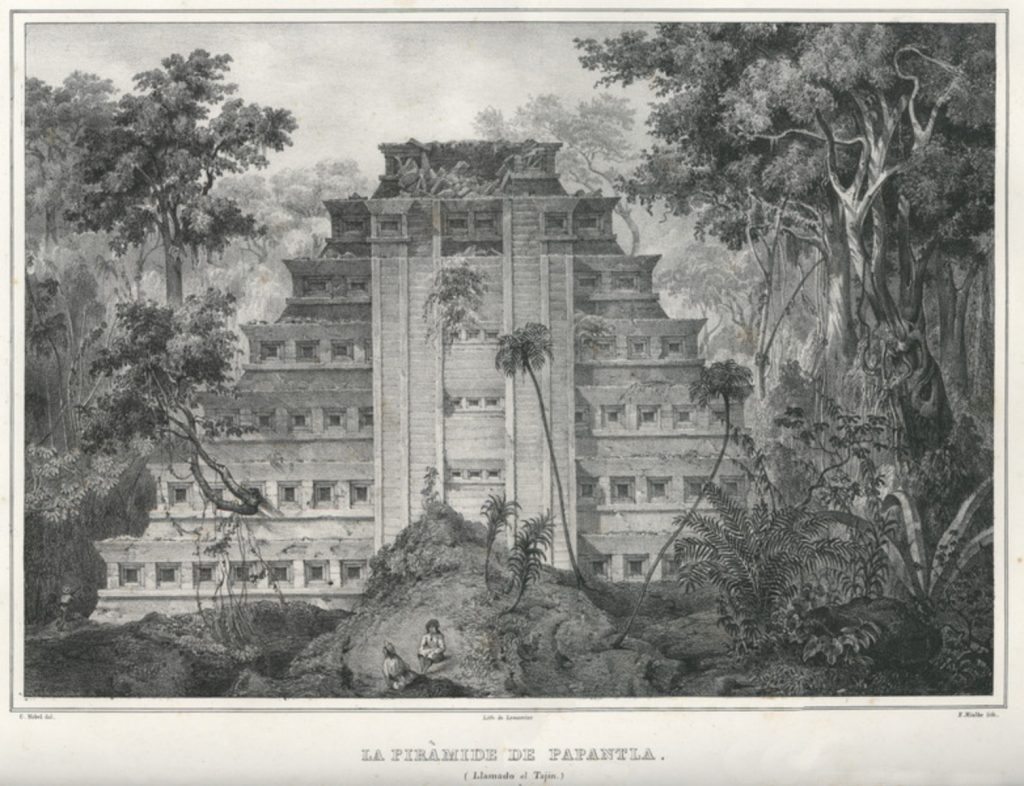

Across the world in Mesoamerica, the residents of what is now known as El Taijin near Mexico City used a lightweight concrete made of pumice, volcanic ash, and lime. The concrete they made is currently well over two-thousand years old and is still in fantastic condition. (Cabrera et al.)

Much of the engineering knowledge of the Greeks and Romans fell out of use during the Middle Ages. The extent to which this knowledge was lost is unknown. However, there are accounts of hydraulic cement being used by medieval masons and some military engineers in the construction of canals, harbors, shipbuilders, and fortresses. (Mukerji)

During the eighteenth century, British and French engineers refined the mixture of hydraulic cement. John Smeaton was a civil engineer by trade and was tasked with building the third Eddystone Lighthouse in the English Channel. This lighthouse is now known as Smeaton’s Tower. Smeaton needed a mortar that would set up in the twelve hours between high tides and so, he performed experiments with different mixtures of limestone, trass, and pozzolanas. He discovered the “hydraulicity” of the cement was directly related to the amount of clay in the limestone used to make it. (Hewlett)

Patented in 1796, James Parker created Parker’s “Roman Cement” which would set in five to fifteen minutes. This was nothing like actual Roman cement and was made by burning septaria nodules that contain clay and calcium carbonate. Other manufactures followed Parker’s lead to create their own versions by burning clay and chalk. (Hewlett)

Portland cement was developed in England in the mid-1800’s and is made from limestone. Joseph Aspdin patented a material he called Portland cement in 1824. Aspdin named it Portland because the color was similar to the stones from the island of Portland, which was a prized material of the time. Aspdin’s cement was not at all like modern Portland Cement, but it was on the right track. (Hewett) His son, William Aspdin accidentally created calcium silicates by firing the mixture with more lime than usual and at a much higher temperature. The mix would set at a reasonable speed and with great strength. This advancement opened up new uses for cement. Later, Isaac Charles Dobson further refined the production of Portland cement by sintering the mix in the kiln. (Hahn and Kemp) The next advancement in Portland cement was the creation of the rotary kiln which would heat the clinker hotter and more evenly forming more alite for stronger cement and allowed for the continuous production of cement in lieu of a batch process.

As humanity grows and improves over time, so does the cement we create. With each advancement in cement technology, we create better lives for ourselves and each other. We are proud to provide the cement to help you build a better future.

Thank you for choosing SACS.

Citations

Brewer, Judy. “The History of Concrete:” The History of Concrete: Textual, 27 Nov. 2012, matse1.matse.illinois.edu/concrete/hist.html.

Hewlett, Peter. Lea’s Chemistry of Cement and Concrete. Elsevier, 2004.

Cabrera, J. G., et al. “Properties and durability of a pre-columbian lightweight concrete.” SP-170: Fourth CANMET/ACI International Conference on Durability of Concrete, vol. 170, 7 Jan. 1997, pp. 1215–1230. Symposium Paper, https://doi.org/10.14359/6874.

Mukerji, Chandra. Impossible Engineering: Technology and Territoriality on the Canal Du Midi. Princeton Univ. Press, 2209.

Hahn, Thomas F., and Emory Leland Kemp. Cement Mills along the Potomac River. West Virginia University Press, 1994.